What is the best way to talk about political ideas ?

Above all, I think the objective should be that we can understand one another clearly. We don’t have to agree, of course, but a large fraction of political disagreements are probably not genuine. They are based in misunderstandings or misinterpretations of statements and positions. Sometimes these misunderstandings are deliberately made or construed in order to “win arguments”. However one useful thing to keep in mind is that political arguments are never “won”, because there is no real “right and wrong”. It’s possible to catch people being inconsistent, but that is usually because political ideas are expressed using poor reasoning or analogies to justify underlying beliefs – which are innate (not “reasoned”). In any case, have you noticed that no matter how many inconsistencies you uncover, the person with whom you are talking does not change his or her political position?

What we should try to do – I think – is work out what these underlying political positions are, when we clear away all the messy, inconsistent reasoning that obscures or is press ganged into justifying them.

There are all sorts of ways we can analyse a political idea. Because things are usually not black or white, I propose that we do this by considering where one’s position lies on a spectrum. The first question we need to answer then is “how many spectra are we going to use?”. Is it even possible to describe a political belief on a sort of graph?

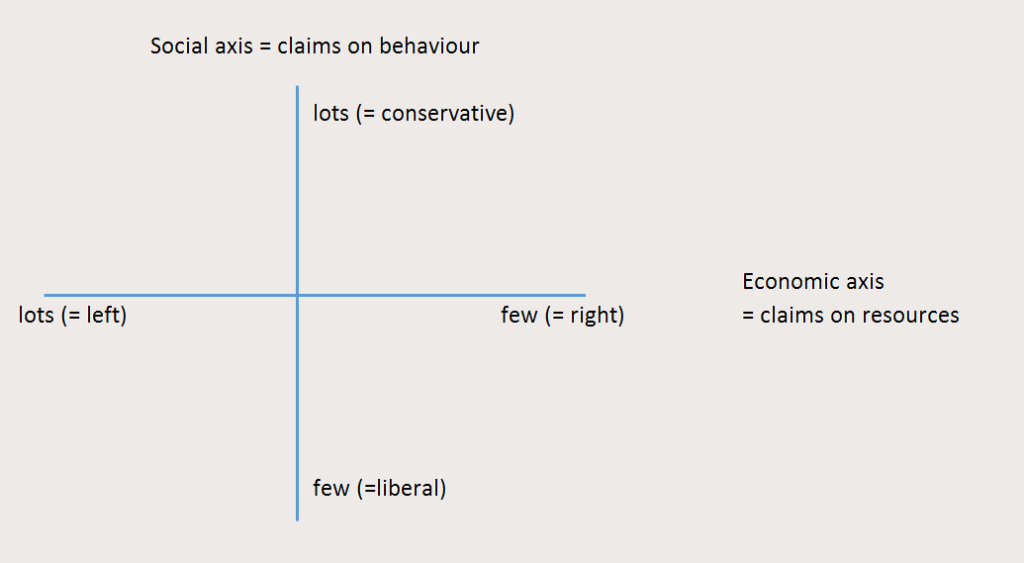

Let’s try to boil them down to two principle “axes” (a recipe with two ingredients if you like). Each axis represents a spectrum of views about a particular issue. You already know one of these – the “left-right” (economic) axis. And most people interested in politics will know the second one – the “liberal-conservative” (social) axis (sometimes described as the “authoritarian – libertarian” or “communitarian – liberal” axis).

We’re going to try to discuss all of our political ideas in terms of these two axes.

This might be a bit of a stretch. Political scientists like Jonathan Haidt think our political opinions actually stem from six innate, moral beliefs. Avi Tuschman boils it down to three. Psychologists think it is possible to break our personalities down to five independent characteristics (referred to as the “big five” or OCEAN). Management consultants like the 4 “axes” – each with two dominant tendencies – which give rise to the 2^4 = 16 Myers-Briggs personalities. All of these methods are doing the same thing we are going to do – trying to break complexity apart into simple components or building blocks in order to understand it better. But they go one level deeper, looking at the underlying genetic or personality dispositions which lead people to adopte a particular morality. We will discuss these underying moralities, but try to stick to the basic expressed political ideas.

—

Politics used to be analysed in terms of the single left-right axis, which dates back to the French Revolution and the ideologies of the elected deputies who grouped themselves on different sides of the National Assembly (royalists versus revolutionaries). It didn’t have to be “left right” – that’s just pure historical chance. It could have been “east-west” if anyone had bothered bringing a compass into parliament. Or “majority minority” (also known as “Bolshevik – Menshevik”), or Whigs and Tories, Radicals and Liberals…

But we are stuck with “left right”. What differentiates political positions on this axis? What does the axis actually measure?

Although left and right may conjure up all sorts of ideologies and positions in your mind, I would like us to think of this axis as strictly “economic”. It’s about Resources with a capital R. Specifically, it’s the axis of “claims on resources”. At one end – the left – people adopt a position which makes extensive claims over (other people’s? everyone’s?) resources in the name of the public interest (justice, equity, fairness etc.), while at the right end of the spectrum much fewer “redistributionary” claims are made.

The other axis can be thought of as a spectrum of “claims on behaviour”. I’m tempted to use the word Reproduction with a capital R instead of behaviour because 1. A lot of the claims on this axis relate to controlling sexuality and sexual freedoms and 2. It makes evolutionary sense to have one axis about access to resources (food), and one about access to reproduction (sex) as being our primary political concerns.

But to keep it broad and simple, I’ll distinguish them as an economic axis about “claims on stuff” and a social axis about “claims on behaviour”. I should perhaps add other people’s into these definitions – but hopefully that goes without saying.

Thus, choosing to give away large amounts of your own resources does not make you “left” on the economic axis, just as choosing to wear conservative clothing does not make you a social “conservative”. What matters in politics is the extent to which you “make claims on others” – in other words, the extent to which you think everyone should share resources, or wear conservative clothing (or any other behaviour), and that the State is justified in coercing people to do this.

—

Note that the social axis is sometimes referred to as “authoritarian – libertarian”, which suggests that social conservatism is the same thing as being “authoritarian” versus a sort of easy-going “live and let live” Big Lebowski Dude personality. This is the sort of value judgement which ideally we’d like to avoid in our discussions (I mean, who wants to be called authoritarian? and who doesn’t want to be “Your Dudeness” ?).

The reason social conservatism is conflated with authoritarianism (or more kindly, “communitarianism”) is because it makes extensive “claims on behaviour”. However keep in mind that the economic axis does something similar – the left makes extensive “claims on resources”, which are backed up with the full force (i.e. authority) of the State. In this respect, they are also “authoritarian”, just about a different subject.

Perhaps one of the reasons that “left wing social liberals” people and “right wing social conservatives” each see their political opponents as fascist bullies is they both feel the “authoritarian nature” of these claims – even though they relate to different axes.

Assuming that “claims on stuff” is pretty straightforward, let’s talk a bit more about “claims on behaviour” here